|

“What's the best type of milk for my toddler?” I get asked this question all the time, and my response is that it depends on why are you planning to give your child milk. I usually get one of these answers:

3) Don’t little kids NEED milk? It is culturally ingrained in us that our kiddos need to drink milk, and to a certain extent, this is true. Mothers’ milk is the first and best source of nourishment for an infant, and meets all of their nutritional needs for at least the first six months of life, which is pretty amazing. For the second six months of infancy, mothers’ milk is still the primary source of nutrition, with some solid foods added in for supplementary nutrients (and oral-motor development, and exploration of new tastes and textures). Historically, our babies would have continued to nurse beyond the first year, into toddlerhood and beyond, and this is still the case in most developing countries, where alternatives are not readily available. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all babies nurse for the first two years of life, minimum, and after that for as long as suits the mother and child. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends breastfeeding for at least one year, and beyond for as long as mutually desired. In spite of this, most babies in the US don’t nurse for 12 months - in part because we have family leave policies that make breastfeeding harder to establish and maintain for working women, as well as heavily promoted alternatives (e.g. infant formula and cow’s milk). However, it may surprise you to know that while most babies in the USA aren’t still nursing at a year, more than a third of them are (36% at 12 months; CDC, 2015), and many will continue beyond this birthday into toddlerhood (1-3 years). Some women may want to introduce a supplementary milk alongside their breastmilk around the first birthday - perhaps to wean their child off the breast, or as an alternative when breastmilk isn’t available (because nobody wants to pump if they don’t have to, amirite?). Some women may decide to stop nursing at a year, and want to switch to a substitute milk. Some women may have stopped nursing sometime during the first year and switched to infant formula, and now they want to know which follow-on milk is right for their toddler. Here’s the rub: in the developed world, after the first year or so, most toddlers need milk less and less for nutritional purposes, because the majority of their nutrient requirements can be increasingly met by solid foods. This is not to say that there’s no benefit in nursing beyond a year! Human milk continues to be a convenient source of many nutrients, which can be particularly useful for picky eaters. It also continues to build the gut microbiome with beneficial bacteria which confers life-long health benefits, plus the longer a women nurses, the lower her rates of breast cancer, and this protective effect against breast cancer is also conferred to the nursing female child. And, last but by no means least, it is a great source of emotional nourishment and security for an increasingly independent child. The genius thing about human milk is that the composition adapts to meet the changing needs of your babe: from morning to night, in sickness and in health, and in different climates. This is also true over time: the fat content of breastmilk increases in the second year for growth and brain development, as do concentrations of lactoferrin (for iron absorption) and certain immunoglobulins (for extra immune support now they're more independent). Plus, in the second year, breastmilk continues to be an excellent source of B12 (94% of RDA), folate (76% of RDA), vitamin A (75% of RDA), and vitamin C (60% of RDA), and a good source of protein (43% of RDA), calcium (36% of RDA), and calories (29% of RDA). (These percentages assume 15 oz of breastmilk per day.) 2) My pediatrician said I should. Most pediatricians will tell you at the one year well-baby visit that you can start introducing cow’s milk now - that’s because you really should not give it to a baby younger than a year, as it can irritate their gut lining and cause intestinal bleeding, plus it can tax their developing kidneys, due to the higher protein content. The message from the medical team here is that after 12 months you may introduce it, rather than that you should introduce it. Remember, the majority of babies whom your pediatrician sees are likely formula-fed by their first birthday, so they may just be assuming that you’re looking for the go ahead to switch your child from formula to cows’ milk (which is much cheaper and more convenient). For breastfeeding mamas who want to continue nursing, there is absolutely no need to introduce an additional milk source to your child. Remember, all toddler milk options are substitutes for breastmilk! Water is a perfectly adequate beverage in between nursing sessions; offer freely throughout the day, especially with meals. As a precautionary tale, I have now encountered a few breastfeeding mothers who introduced cow’s milk at one year, on their pediatrician’s advice, and found that their little one ended up weaning from the breast prematurely. Some of these toddlers lost interest in breastmilk when they realized they could just get cows’ milk in a cup, whenever they wanted, and maternal supply dropped. In more than one of these cases, mothers developed mastitis due to blocked milk ducts, and this lead to terminating the breastfeeding relationship earlier than intended when antibiotics were needed. For women who have stopped nursing, or would like to, there are options:

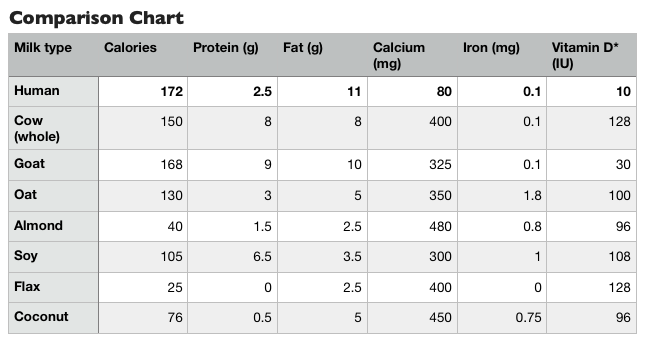

So which is closest to human milk? It depends on the nutritional category (check out the chart above). Goats' and cows' milk are the closest on calorie and fat content, but have more than three times the protein, and four to five times the calcium. This isn’t necessarily a case of more is better - remember, cow and goat milks are nature’s perfect nutrition source for baby cows and goats, not baby humans! The proteins in goats' milk are more similar to those in human milk, and overall the nutrient profile of goats' is closest to humans'. All of the plant milks are low-fat compared with mammal milks, and toddlers need adequate fat in their diets for optimal growth and brain development. The milk with the closest protein content to human milk is oat milk, and it’s also the closest in calories and fat out of the plant milks, plus it has the most iron. All of the milks have higher vitamin D content than breast milk, because it’s added by manufacturers to both cows’ milk and plant milks; you can also boost the vitamin D content of human milk with a high dose supplement (mother takes 6,400 IU per day), or supplement the child directly, per the AAP guidelines (600 IU per day). All of the milks have higher calcium content than breastmilk too - plant milks are trying to match up to cows’ milk, so they fortify with calcium to meet those levels (even if this isn’t what nature designs for human babies). Some of these alternatives are very low calorie and and don’t offer much nutrition (e.g. almond milk and flax milk). They are still more nutritious than water, so if that’s what they’re replacing in the child’s diet, then it’s likely not a problem. But, sometimes milk drinking (of all varieties) can crowd out more nutrient dense foods by filling up the child’s stomach, especially if the milks being offered are sweetened and easy to guzzle. All supplementary milk can be offered in a cup at this age, not a bottle - toddlers are developmentally ready for an open cup, and this makes milk drinking more of an intentional activity, so they’re less likely to fill up on it. Also, given the high levels of added calcium in all of the alternative milks, plus the risk of iron deficiency anemia in this age group, it is better to offer milks separately from iron-rich meals (e.g. meat and beans), as calcium inhibits iron absorption. The bottom line for all of these milk options is that none of them exactly matches the nutrition of human breastmilk, but that doesn't matter much if they are offered as part of a well balanced and varied diet of solid foods, rather than being the main source of nutrition. During the second year of life, solid foods are increasingly the main source of nutrients for the toddler, shifting from maybe 50 percent of nutrients coming from food (50 percent from milk) at one year old, to around 75 percent of nutrients coming from foods at two years old, and 90 percent or more at three years old. However, if you have a very picky eater on your hands, who is still heavily reliant on milk for nutrition, you may want to consult with a nutritionist or well-versed pediatrician on which is best for them (and trouble shoot their finicky feeding behaviors while you’re at it!). 1) How will they get enough calcium/protein/vit D without milk?

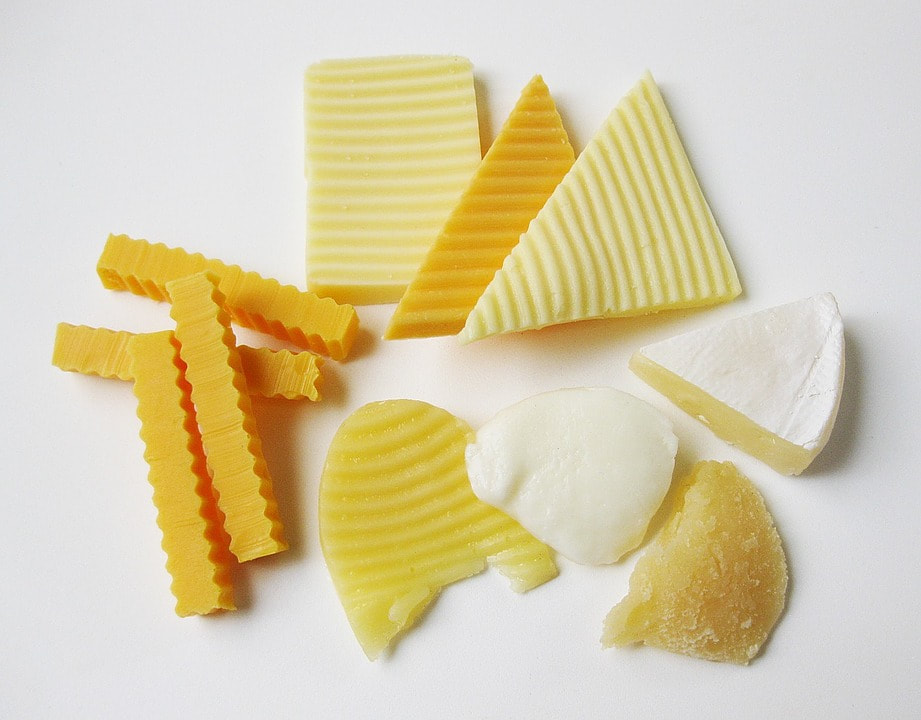

I hope you now understand that none of these milks are truly necessary, just a convenient way to supplement the toddler's diet, particularly in terms of the calcium and vitamin D content. So, if your little one just isn’t into drinking milk, period, don’t sweat it - it’s not some essential elixir for them to reach their full growth potential. Calcium is important for development of strong and healthy bones, as well as muscle function, and toddlers need ~700 mg/day. Vitamin D is essential for absorption of calcium, and immune function; children in this age group (1-3 years old) need 600 IU/day. The AAP says that toddlers can get enough calcium and vitamin D each day from eight to sixteen ounces (1-2 cups) of cow's milk, or the equivalent amount of other dairy products, like yogurt or cheese. 1 cup of milk is equivalent to 1 cup of yogurt, or 1.5 oz of cheese, or 1 cup of calcium-fortified plant milk. So, if your toddler doesn’t drink milk but eats a half cup of yogurt for breakfast and a string cheese for lunch, that’s the equivalent of a cup (8 oz) of milk. Cultured dairy products like yogurt and cheese can be easier to digest, due to the fermentation process breaking down the casein proteins - many people who have a hard time drinking milk can consume yogurt and cheeses without issue, for this reason. So, if your child seems to have a slight dairy sensitivity, but not an allergy, they may have no problems with cheese and yogurt. Harder, more mature cheeses (e.g. Cheddar) are easier on the stomach than softer, younger cheeses (e.g. ricotta), as they have been cultured longer. Greek yogurt has the liquid (whey) strained out, making the protein (casein) content more concentrated, so a thinner plain yogurt or kefir can be easier to tolerate due to the lower casein content. Also, cooked/baked in milk is often fine for people with mild sensitivities, as the cooking process denatures the proteins. Really, the ‘dairy’ category is a pseudonym for calcium foods, because dairy is good source of this mineral: a cup of milk provides 300mg, half a cup of yogurt provides 200mg, 1 ounce of cheese provides ~200 mg. Other calcium-rich foods outside of the dairy family include soy products (1/2 cup of tofu, calcium fortified = 215 mg), seeds (1oz chia seeds = 180 mg), grains (1/4 of oatmeal = 45 mg), vegetables (1/4 cup of broccoli = 50 mg), and some fruits (1 dried fig = 35 mg). The AAP actually recommends limiting all milk and dairy products for toddlers, to no more than 2 cups a day for 1-year-olds, and no more than 3 cups a day for 3-year-olds, to reduce the risk of nutrient deficiencies, especially iron. Iron deficiency is fairly common in this age group, and is clearly linked with consumption of cow’s milk. Vitamin D is not typically added to dairy products other than milk, so you’d need to consider other sources of vitamin D if your child isn’t drinking a fortified milk. There aren’t very many food sources of vitamin D (we have evolved to get it from the sunshine rather than relying on food). 1 oz of sockeye salmon has around 150-250 IU (wild caught has more), and an egg yolk has around 40 IU (eggs from pasture-raised hens can have double this). Some orange juice is also fortified with vitamin D, however, fruit juices aren’t recommended for toddlers due to the high sugar content, and the fructose (fruit sugars) can cause diarrhea in tiny tummies (limit to 2-4oz if you do offer it, and dilute 50:50 with water). Vitamin D deficiency is common, due to the fact that most of us do not spend a lot of time outside, and we often protect our little ones from sun exposure when they are outside, with sun screens, hats, and protective clothing. Rickets is a condition arising from inadequate vitamin D, and calcium - bones are weakened, because vitamin D is need for calcium absorption. This condition is rare, but it is actually on the rise in some developed countries; in toddlers, the most common sign is bowing of the legs. Most milks (plant and mammal) are enriched with vitamin D, but look out for the type of D - in both fortified foods and supplements, you want vitamin D3, not D2, which your body can't really absorb. Also, vitamin D is fat-soluble, so if you’re drinking a fat-free milk fortified with D, you probably aren’t getting any of the benefits! As for protein, toddlers really don't need a whole lot. The average toddler (1-3 years old) needs around 16 grams per day to grow adequately. To personalize for your child, it's 0.55 grams of protein per pound of body weight. Two cups of cows' milk (16 oz) has 16 grams of protein. One egg has 6g, 1 oz of meat or fish has 7g (that's roughly the size of the top of your thumb). 1/4 cup of beans has ~ 4g, half a slice of bread has 1-2g, and 1 tablespoon of nut butter has ~3g. It's very easy to meet the protein needs of a toddler without milk! And, too much protein can tax their kidneys - twice the RDA is a good guide for an upper limit (1.1g/lb); for a 25 lb toddler, this would be ~25 grams protein/day. Summary:

0 Comments

|

AuthorHi, I'm Amy. I'm a nutritionist in the DC area, working with clients of all ages, focusing on prenatal and pediatrics. I'm all about straightforward, evidence-based health & wellness advice - because life/parenting in the modern world is complicated enough! Categories

All

November 2022

|

Seed to Sapling Nutrition

RSS Feed

RSS Feed